This article is part of our 'What's next? Key issues for the Sixth Senedd' collection.

The Fifth Senedd saw a move away from austerity and ended with massive public spending to deal with the pandemic. How has spending changed? And what pressures lie ahead for Wales?

Spending on public services since the 2008 financial crisis has largely been characterised by austerity.

At the Spending Round in September 2019, the UK Government signalled it was “turning the page on austerity and beginning a new decade of renewal”. The Welsh Government’s 2019-20 and 2020-21 budgets were subsequently referred to as “a step-change in the path of the Welsh resource budget”.

Budgets in the Fifth Senedd

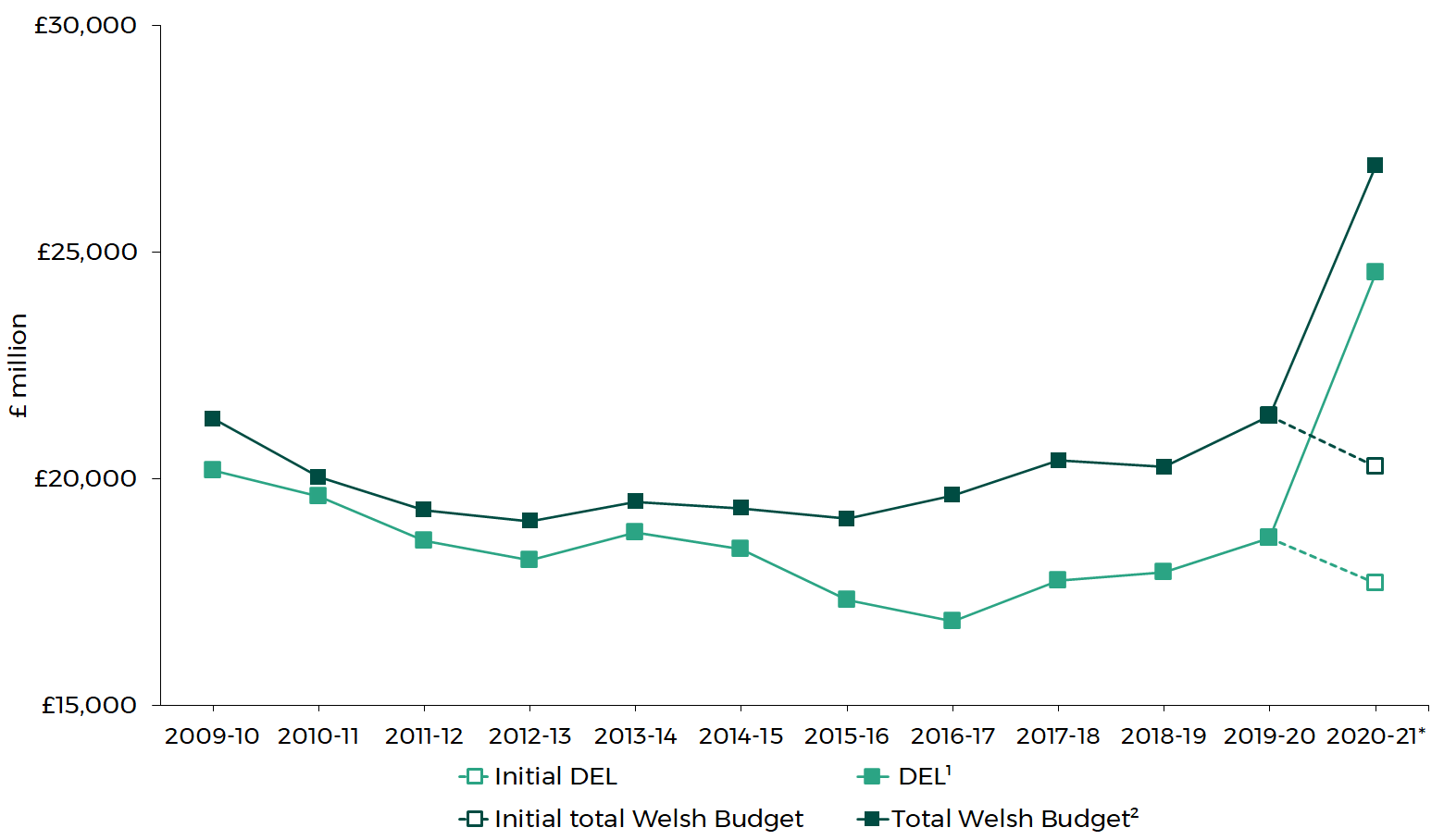

While budgets in the Fifth Senedd saw an increase in the Welsh Government’s spending power, it’s only since 2019-20 that the total Welsh budget has increased to levels above 2009-10 (in real terms). Even with that, spending on Welsh Government departments has generally remained below historic levels.

Welsh Government Budget, 2009-10 to 2020-21 (2020-21 prices, £ million)

Source: Welsh Government budgets and GDP Deflators (March 2021)

Notes:

¹DEL = Departmental Expenditure Limit: the discretionary part of the budget that the Welsh Government chooses how to spend

²Total Welsh Budget: includes all funding available for the Welsh block grant less the amount for the Wales Office

*Figures at most recent Supplementary Budget. For 2020-21, figures at the Final Budget, March 2020 (dashed) and those at the Third Supplementary Budget (February 2021) are included. Real terms figures reflect atypical movement in the 2020-21 GDP deflator.

The pandemic meant spending in 2020-21 looks very different to initial proposals. The Welsh Government’s Third Supplementary Budget 2020-21 allocated almost £25 billion to departments, a significant increase from the £18 billion originally planned.

While the Welsh Government reprioritised some departmental spend, most of the increase is the result of spending decisions around the pandemic in England. The current budget for 2021-22 therefore sees a decrease in overall allocations to around £20 billion.

Health and Social Services is consistently the biggest area of Welsh Government spending. In terms of day-to-day revenue spending it takes up over half of the 2021-22 budget. Alongside Housing and Local Government, the next largest area of Welsh Government expenditure, those two areas make up around 80% of departmental revenue budgets in 2021-22.

The Fiscal Framework

The rules around Welsh Government funding are set out in the Fiscal Framework. Most of the Welsh Government’s money comes through the Welsh block grant, linked to UK Government spending through the Barnett Formula. This arrangement was bypassed to some extent during the pandemic, with the UK Government offering a ‘guarantee’ of funding.

|

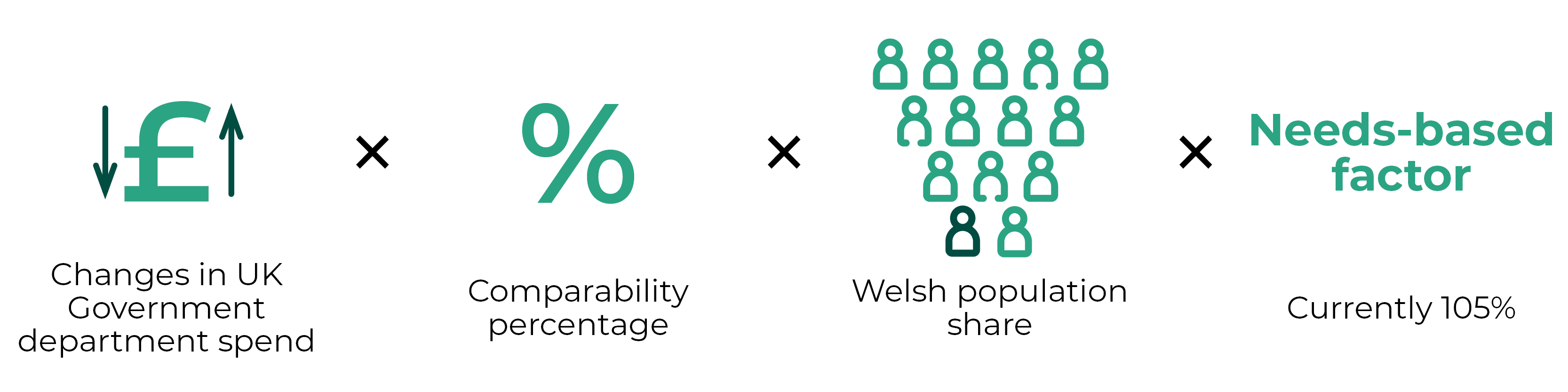

How the Barnett Formula works The Barnett formula calculates the annual change in the block grant. It uses the annual change in a UK Government department’s budget and applies a comparability percentage based on the extent to which that department’s services are devolved, it also takes into account the relative population of Wales. Wales also has a block grant floor, which ensures Wales’ funding will converge to a level in line with Wales’ needs. It is set at 115%. Currently the needs based factor is 105% as Wales’ relative funding per head is around 120%. Once Wales’ relative funding reaches 115% of England’s, the multiplier will be locked at 115%.

|

Other fiscal measures were perhaps not flexible enough when put under the strain of the pandemic. The Wales Reserve is capped at £350 million and limited to an annual maximum drawdown of £125 million revenue and £50 million capital. The significant COVID-19 funding that came to Wales at the end of 2020-21, due to policy decisions in England, meant more flexibility was required to carry forward up to an additional £650 million.

On the other hand, the Welsh Government hasn’t used all of the fiscal tools at its disposal. It can borrow up to £150 million capital annually, but hasn’t done so in 2019-20 or 2020-21.

These issues led the Fifth Senedd’s Finance Committee to suggest that funding mechanisms needed urgent review. The Committee suggested:

- capital borrowing limits should be increased;

- there should be greater flexibility around the Wales Reserve; and

- there should be an independent process for challenging funding decisions, noting the UK Government acted as ‘judge and jury’ when it comes to Wales’ funding arrangements.

New powers for UK investment in Wales

The Internal Market Act 2020 allows the UK Government to provide financial assistance for various purposes (see our article on Wales in the UK) anywhere in the UK. It gives the UK Government new powers to directly fund activity in devolved policy areas.

Two specific funds will take advantage of these powers:

- the UK Shared Prosperity Fund (starting with the UK Community Renewal Fund), which will replace EU structural funds; and

- the ‘Levelling Up Fund’. Initially a fund for England, but subsequently extended to cover the whole of the UK.

Debate around the use of these powers has already begun.

The previous Welsh Government suggested the UK Government planned to “bypass the devolution settlement” and the three Finance Ministers of the devolved nations issued a joint statement in March stating the UK Government was “ignoring [their] respective devolution arrangements”.

However, the Secretary of State for Wales, Simon Hart, suggested funds would have “a greater degree of local input” and that they represented an “extension of the devolution process”.

It’s unclear how or whether the Welsh Government will be involved in these spending decisions, and how they will be scrutinised.

Familiar but significant pressures ahead?

The costs of the pandemic will undoubtedly shape the future of public sector finances. UK Government borrowing is due to hit a peacetime high of £355 billion in 2020-21 and forecast at £234 billion for 2021-22. Headline debt for the UK is due to hit 100% of GDP in 2020-21 (see article on economic recovery).

At the UK Government Budget in March 2021 the Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, outlined the need to “begin the work of fixing our public finances”. The Chancellor now plans to spend between £14-17 billion a year less on public services each year after 2021, than was planned prior to the pandemic. It’s been suggested that medium-term spending plans make for “a more austere outlook for the Welsh budget and Welsh public services”.

The implications of the pandemic for public finances won’t just be in terms of immediate financing of the response, but the long term pressures it creates for services. The previous Welsh Government allocated £320 million for a reconstruction package and £225 million for a capital stimulus package. The costs of recovery are only likely to increase.

It’s been suggested that the NHS and Social Care in England would need an additional £12 billion a year to make up lost ground. In Wales, the NHS waiting list reached a record high of 549,353 in February 2021 (see article on NHS waiting times). The previous Minister for Health and Social Services, Vaughan Gething, estimated recovery would take at “least a full Senedd term”. A recovery plan for Health published in March outlined an “initial” £100 million of funding.

Similarly, school closures led to the previous Welsh Government providing additional funding for pupils (see article on education in the time of COVID), but the scale and costs for pupils to ‘catch-up properly’ could be as much as “half a year of schooling”, around £1.4 billion.

Others have called on the Welsh Government to exploit the opportunities that recovery presents to build back greener, including investing in green infrastructure, transforming transport and public spaces, and promoting remote working.

Analysis suggests funding these pressures could lead to a return to austerity for parts of the Welsh Government’s budget, based on current UK Government spending plans. How these pressures emerge and are addressed will be a driving force for policy and spending decisions in the Sixth Senedd.

Article by Owen Holzinger, Senedd Research, Welsh Parliament